Supplies that were likely stored in the vessel-including barrels of water, pork, beef, rice, rum, molasses, flour, and bread-may still lie buried in the ship’s hold. “Sometimes, things are exposed that haven’t previously been exposed then get covered again.”Ī “limited and targeted” excavation of the wreck is planned for March, Delgado says. Sometimes it comes off, sometimes it goes on,” Delgado says, likening the movement to a tide coming in and out. “We now know the mud that’s on the site does move. “Just knowing my ancestors were documented, the books that were written. “The ship in itself doesn't make it real for me,” Davis says. And that somewhere out there in the Mobile River lay the remains of the vessel. That Foster had tried to destroy the evidence of his crime by burning and scuttling the Clotilda.

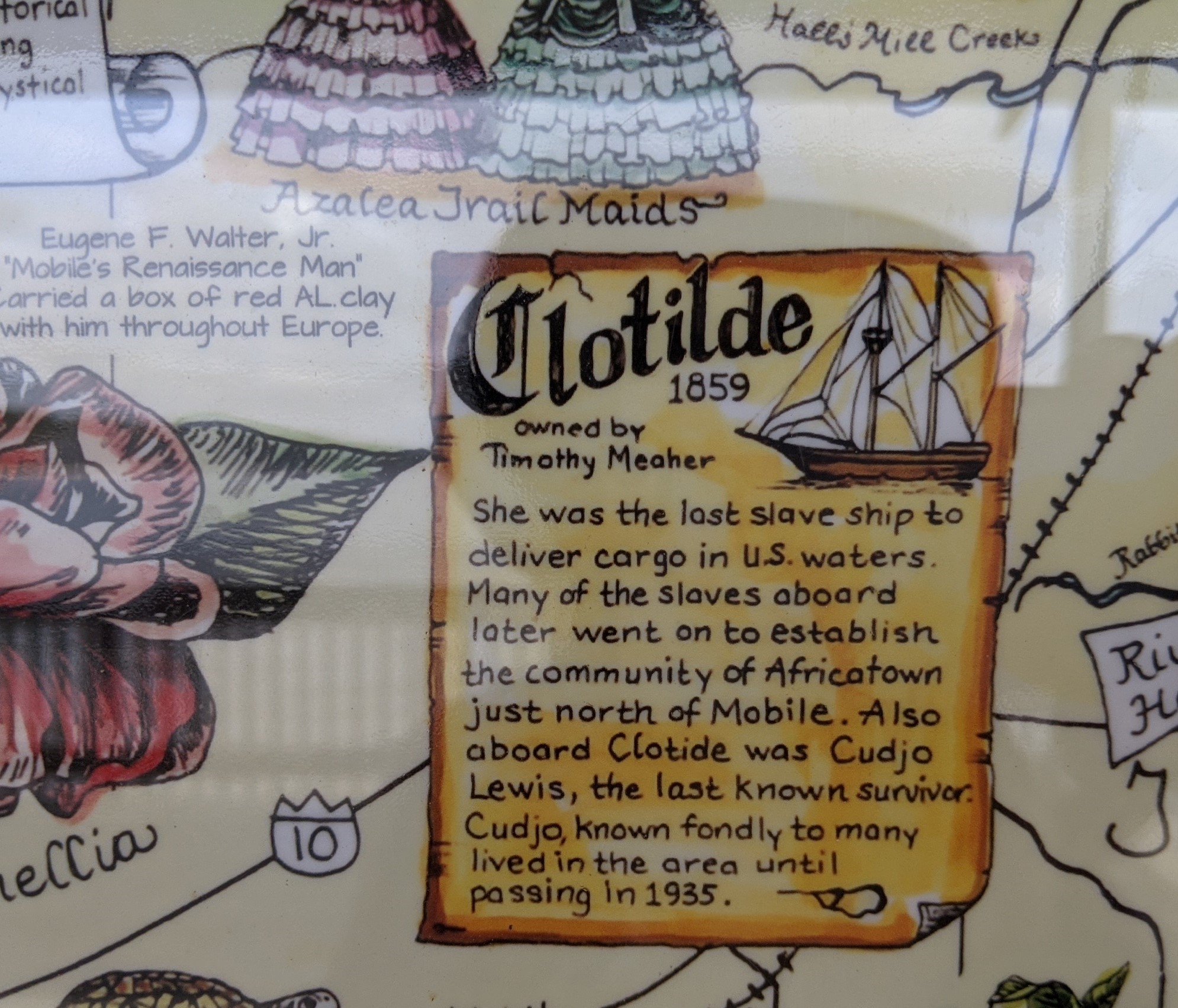

That the Clotilda’s captain, William Foster, returned from Africa in 1860 with 108 captives on board-including Charlie Lewis, Davis’s ancestor and one of the founders of Africatown. Growing up in historic Africatown near Mobile, Alabama, Davis always believed the stories she heard about the origin of her community: That a wealthy white businessman made a bet that he could import enslaved Africans into Mobile, long after the practice had been outlawed. When the 160-year-old wreckage of the Clotilda, America’s last known slave ship, was positively identified in the murky waters of the Mobile River in 2019, that was enough for Joycelyn Davis.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)